On 22 January 2021, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) entered into force. The 54 states parties are prohibited from possessing nuclear weapons as assisting nuclear weapons programmes and alliances that rely on nuclear deterrence. The TPNW builds on similar multilateral prohibitions of biological and chemical weapons. Proponents of the TPNW argue that the treaty thus closes a major gap in international law because there are now comprehensive, legally-binding bans on all types weapons of mass destruction.

The TPNW is the first modern multilateral disarmament treaty which the Federal Republic of Germany resolutely rejects and was absent from its negotiation. As a consequence, Germany is wasting an opportunity to make use of the political momentum created by the TPNW towards a world free of nuclear weapons. Acccession to the ban treaty may currently not be a realistic option for Berlin. But Germany should increase the elbow room for its nuclear disarmament policies by shifting to a proactive policy of constructive engagement with the TPNW.

Accession remains costly

The government has some good reasons for not signing the TPNW. In the short term, the political costs of joining would be high. Accession would isolate Germany within NATO. The Alliance, led by the nuclear weapons states France, United Kingdom and United States, fundamentally rejects the TPNW.

NATO refers to itself as a “nuclear alliance”. Participation in the Alliance’s nuclear sharing arrangements is incompatible with the TPNW. The treaty prohibits not only the possession and stockpiling of nuclear weapons but also their use and threat of use — in other words, nuclear deterrence.

The German government also criticises the ban treaty’s inherent weaknesses and it points to an alleged incompatibility with the nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT). These arguments are less sound. Occasionally, critics apply the yardsticks of traditional nuclear arms control agreements, such as New START, to the ban treaty, for example with regard to definitional clarity or the verifiability of the treaty provisions.

Stigmatizing nuclear weapons

The TPNW, however, is not a classic arms control treaty, concluded by nuclear weapons states with the intention of constraining the nuclear arms race. Nearly all of the 122 non-nuclear weapons states in 2017 that negotiated the ban treaty at the UN General Assembly reject what they see as the nuclear weapons states’ self-serving arguments for preserving nuclear deterrence. TPNW supporters have decided to place “their” treaty in the tradition of humanitarian arms control. In doing so, they build on legally-binding prohibitions of anti-personnel mines or cluster munitions. These agreements, too, were negotiated in the face of bitter opposition by powerful possessor states and exert political pressure primarily by stigmatizing inhumane weapons.

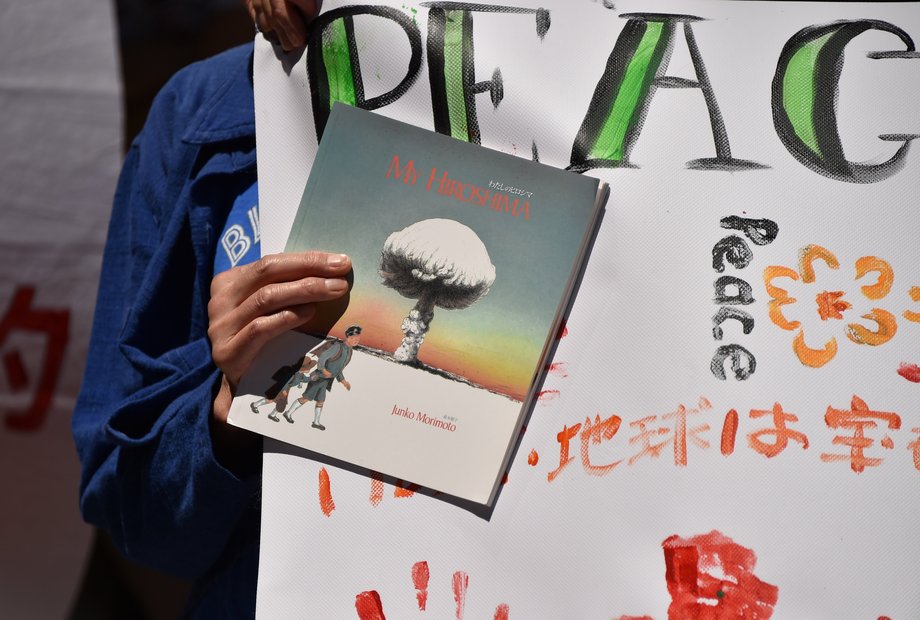

The primary objective of the TPNW, therefore, is to change perceptions of nuclear deterrence. The treaty places particular emphasis on the horrendous human and environmental consequences of nuclear weapons programmes and a potential nuclear weapons use. Supporters of the treaty also argue that the use of nuclear weapons is incompatible with the requirements of international humanitarian law, for example the requirement of discriminating in war between civilians and combatants or the preventing the unnecessary suffering of victims. They thus reveal the contradictions inherent in nuclear deterrence.

Increasing influence

As a result of the confusion about disarmament yardsticks, deterrence advocates and treaty supporters often talk — pointedly and sometimes intentionally— at cross purposes. One side stresses the supposed security benefits of nuclear deterrence while the other side highlights nuclear risks and humanitarian costs of nuclear weapons.

From the German perspective, this drifting apart of the two sides of the debate about the role of nuclear weapons is worrisome. In the long term, it could contribute to a scenario in which the TPNW is seen as an NPT competitor. For 50 years, the NPT has been the most important and indispensable framework for collectively dealing with problems related to nuclear disarmament and the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, as well as the monitoring of the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

With 191 states parties, the NPT is nearing universality. Nuclear weapons possessor states India, Israel, North Korea and Pakistan are the only non-states parties. The TPNW is nowhere close to having this kind of global coverage, even if a majority of states voted for the treaty in July 2017 and around one-third of the world’s population lives in countries that signed the TPNW. Ban treaty opponents are politically and militarily powerful: the nine nuclear weapons possessors and the roughly 40 allies of nuclear weapon states account for approximately 85% of global defence spending (TPNW party states: 2%) and 96% of arms exports worldwide (TPNW party states: 0.6%). It is not surprising that the ban treaty has been described as a movement of the weak against the strong.

Germany’s security depends on the ability to influence debates about the role of nuclear weapons. For Berlin, it is thus particularly important to prevent a looming fragmentation of the nuclear order. To achieve this goal, Germany has to be willing to sit at the table with all sides. Berlin must be able to speak with its nuclear allies in NATO as well as with disarmament advocates and TPNW supporters. Those who argue that Germany is involved in NATO nuclear sharing because these arrangements provide opportunities to influence nuclear policies, should, for exactly the same reason, endorse a constructive debate on the TPNW.

Two components of constructive engagement

Thus, it is a central challenge for Germany to create opportunities for constructive engagement short of TPNW accession. Two measures are particularly well-suited to take up the TPNW’s positive momentum and, in doing so, create elbow room on nuclear disarmament.

First, Germany should to commit to participate as an observer in the first conference of TPNW states parties. This would provide Berlin with opportunities to introduce constructive suggestions to address aspects of the treaty that are problematic from a German perspective, such as the NPT’s relation vis-à-vis the TPNW and more stringent verification provisions. The TPNW expressly foresees that relevant non-governmental organisations, international organisations and institutions as well as states that are not party to the treaty be invited to observe meetings of states parties, which the UN Secretary-General must convene within one year of entry into force. However, states not party to the TPNW must pay a share of the cost of the conference, based on the UN scale of assessment. As a result, participation could put Germany in the odd situation of being the largest financial contributor to a conference of states parties under a treaty that Berlin currently does not intend to join. To ameliorate this problem, Berlin could try to convince the 16 participants of the Stockholm Initiative to collectively take part in the TPNW conference of states parties, either as observers or states parties. Germany and Sweden launched this disarmament initiative, inter alia, to build bridges between TPNW supporters and critics. The Stockholm Initiative counts among its members political (and financial!) heavyweights such as Japan. Recently, co-chair Sweden has announced its intention to observe the meeting of states parties. It would increase the legitimacy of the group as a bridge-building exercise if Germany were to follow suit.

Second, Germany should work within NATO towards more transparency of nuclear doctrines. Proponents and opponents of the TPNW should share an interest in debating whether and how international humanitarian law requirements can be observed in nuclear war planning. The goal is not to make highly classified nuclear weapons operational plans public. Rather, the nuclear weapons weapon states can and should describe the procedures by which they aim to ensure the conformity of nuclear warfighting plans with the rules of international humanitarian law. It is known, for example, that the US Department of Defense includes international law experts in nuclear war planning and that international lawyers advise the US president before he or she would authorise nuclear weapons use. Other nuclear weapons states likely have (or should have) similar procedures in place. Germany participates in NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group and is thus itself is involved in planning, exercising and, ultimately, deploying nuclear weapons. It is therefore important for Berlin to clarify how NATO’s nuclear weapons planning process takes international law requirements into account. Such a discussion could also help to limit the circumstances under which nuclear weapons might be used. The new US president Joe Biden, for example, is open to the idea that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons should be to deter a nuclear attack.

Despite all their political differences, critics and advocates of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons are united on one issue: We need more debate in Germany about the role of nuclear weapons in security policies. Norway, Sweden and Switzerland have established commissions, which have contributed to domestic discussions on the TPNW. Such an inclusive and open-ended exchange of arguments could also help Germany to increase awareness about of nuclear weapons control and help to make decisions on deterrence and disarmament more democratic.

You can contact the author Dr Oliver Meier via his email meier@![]() ifsh.de .

ifsh.de .

What would happen if an atomic bomb were to explode over Hamburg was presented by IFSH in an animated explanatory video with English subtitle (YouTube link).